| Look up rat in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Rats Temporal range: Early Pleistocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| The brown rat (Rattus norvegicus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Muridae |

| Subfamily: | Murinae |

| Genus: | Rattus Fischer de Waldheim, 1803 |

| Species | |

| Synonyms | |

Stenomys Thomas, 1910

| |

"True rats" are members of the genus Rattus, the most important of which to humans are the black rat, Rattus rattus, and the brown rat, Rattus norvegicus. Many members of other rodent genera and families are also referred to as rats, and share many characteristics with true rats.

Rats are typically distinguished from mice by their size. Generally, when someone discovers a large muroid rodent, its common nameincludes the term rat, while if it is smaller, the name includes the term mouse. The muroid family is broad and complex, and the common terms rat and mouse are not taxonomically specific. Scientifically, the terms are not confined to members of the Rattus and Mus genera, for example, the pack rat and cotton mouse.

Contents

[hide]Species and description

The best-known rat species are the black rat (Rattus rattus) and the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). The group is generally known as the Old World rats or true rats, and originated in Asia. Rats are bigger than most Old World mice, which are their relatives, but seldom weigh over 500 grams (1.1 lb) in the wild.[1]

The term "rat" is also used in the names of other small mammals which are not true rats. Examples include the North American pack rats, a number of species loosely called kangaroo rats, and others. Rats such as the bandicoot rat (Bandicota bengalensis) are murine rodents related to true rats, but are not members of the genus Rattus. Male rats are called bucks, unmated females are called does, pregnant or parent females are called dams, and infants are called kittens or pups. A group of rats is referred to as a mischief.[2]

The common species are opportunistic survivors and often live with and near humans; therefore, they are known as commensals. They may cause substantial food losses, especially in developing countries.[3] However, the widely distributed and problematic commensal species of rats are a minority in this diverse genus. Many species of rats are island endemics and some have become endangered due to habitat loss or competition with the brown, black or Polynesian rat.[4]

Wild rodents, including rats, can carry many different zoonotic pathogens, such as Leptospira, Toxoplasma gondii, and Campylobacter.[5] The Black Death is traditionally believed to have been caused by the micro-organism Yersinia pestis, carried by the tropical rat flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) which preyed on black rats living in European cities during the epidemic outbreaks of the Middle Ages; these rats were used as transport hosts. Another zoonotic disease linked to the rat is the foot-and-mouth disease.[6]

The average lifespan of any given rat depends on which species is being discussed, but many only live about a year due to predation.[7]

The black and brown rats diverged from other Old World rats during the beginning of the Pleistocene in the forests of Asia.[8]

Rat tails

The characteristic long tail of most rodents is a feature that has been extensively studied in various rat species models, which subsequently suggest three primary functions of this structure: thermoregulation, minor proprioception, and a nocifensive-mediated degloving response. Rodent tails—particularly in rat models—have been implicated with a thermoregulation function that follows from its anatomical construction. This particular tail morphology is evident across the family Muridae (in contrast to the bushier tails of the squirrel family, Sciuridae). The tail is hairless and thin-skinned, but highly vascularized, thus allowing for efficient counter-current heat exchange with the environment. The high muscular and connective tissue densities of the tail, along with ample muscle attachment sites along its plentiful caudal vertebrae facilitate specific proprioceptive senses to help orient the rodent in a three dimensional environment. Lastly, murids have evolved a unique defense mechanism termed "degloving" which allows for escape from predation through the loss of the outermost integument layer on the tail. However, this mechanism is associated with multiple pathologies that have been the subject of investigation.

Multiple studies have explored the thermoregulatory capacity of rodent tails by subjecting test organisms to varying levels of physical activity and quantifying heat conduction via the animals' tails. One study demonstrated a significant disparity in heat dissipation from a rat's tail relative to its abdomen.[9] This observation was attributed to the higher proportion of vascularity in the tail, as well as its higher surface area to volume ratio, which directly relates to heat's ability to dissipate via the skin. These findings were confirmed in a separate study analyzing the relationships of heat storage and mechanical efficiency in rodents that exercise in warm environments. In this study, the tail was a focal point in measuring heat accumulation and modulation.

On the other hand, the tail's ability to function as a proprioceptive sensor/modulator has also been investigated. As aforementioned, the tail demonstrates a high degree of muscularization and subsequent innervation that ostensibly collaborate in orienting the organism.[10]Specifically, this is accomplished by coordinated flexion and extension of tail muscles to produce slight shifts in the organism's center of mass, orientation, etc., which ultimately assists it with achieving a state of proprioceptive balance in its environment. Further mechanobiological investigations of the constituent tendons in the tail of the rat have identified multiple factors that influence how the organism navigates its environment with this structure. A particular example is that of a study in which the morphology of these tendons is explicated in detail.[11] Namely, cell viability tests of tendons of the rat's tail demonstrate a higher proportion of living fibroblasts that produce the collagen for these fibers. As in humans, these tendons contain a high density of golgi tendon organs that help the animal assess stretching of muscle in situ and adjust accordingly by relaying the information to higher cortical areas associated with balance, proprioception, and movement.

The characteristic tail of Murids also displays a unique defense mechanism known as "degloving" in which the outer layer of the integument can be detached in order to facilitate the animal's escape from a predator. This evolutionary selective pressure has persisted despite a multitude of pathologies that can manifest upon shedding part of the tail and exposing more interior elements to the environment.[12]Paramount among these are bacterial and viral infection, as the high density of vascular tissue within the tail becomes exposed upon avulsion or similar injury to the structure. The degloving response is a nocifensive response, meaning that it occurs when the animal is subjected to acute pain, such as when a predator snatches the organism by the tail.

As pets

Specially bred rats have been kept as pets at least since the late 19th century. Pet rats are typically variants of the species brown rat, but black rats and giant pouched rats are also known to be kept. Pet rats behave differently from their wild counterparts depending on how many generations they have been kept as pets.[13] Pet rats do not pose any more of a health risk than pets such as cats or dogs.[14] Tamed rats are generally friendly and can be taught to perform selected behaviors.

As subjects for scientific research

In 1895, Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts (United States) established a population of domestic albino brown rats to study the effects of diet and for other physiological studies. Over the years, rats have been used in many experimental studies, which have added to our understanding of genetics, diseases, the effects of drugs, and other topics that have provided a great benefit for the health and well-being of humankind. The aortic arches of the rat are among the most commonly studied in murine models due to marked anatomical homology to the human cardiovascular system.[15] Both rat and human aortic arches exhibit subsequent branching of the brachiocephalic trunk, left common cartoid artery and left subclavian artery, as well as geometrically similar, non-planar curvature in the aortic branches.[15] Aortic arches studied in rats exhibit abnormalities similar to those of humans, including altered pulmonary arteries and double or absent aortic arches.[16] Despite existing anatomical analogy in the inthrathoracic position of the heart itself, the murine model of the heart and its structures remains a valuable tool for studies of human cardiovascular conditions.[17]

Laboratory rats have also proved valuable in psychological studies of learning and other mental processes (Barnett, 2002), as well as to understand group behavior and overcrowding (with the work of John B. Calhoun on behavioral sink). A 2007 study found rats to possess metacognition, a mental ability previously only documented in humans and some primates.[18][19]

Domestic rats differ from wild rats in many ways. They are calmer and less likely to bite; they can tolerate greater crowding; they breed earlier and produce more offspring; and their brains, livers, kidneys, adrenal glands, and hearts are smaller (Barnett 2002).

Brown rats are often used as model organisms for scientific research. Since the publication of the rat genome sequence,[20] and other advances, such as the creation of a rat SNP chip, and the production of knockout rats, the laboratory rat has become a useful genetic tool, although not as popular as mice. When it comes to conducting tests related to intelligence, learning, and drug abuse, rats are a popular choice due to their high intelligence, ingenuity, aggressiveness, and adaptability. Their psychology, in many ways, seems to be similar to humans. Entirely new breeds or "lines" of brown rats, such as the Wistar rat, have been bred for use in laboratories. Much of the genome of Rattus norvegicus has been sequenced.[21]

General intelligence

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (January 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Because of evident displays of their ability to learn,[22] rats were investigated early to see whether they exhibit general intelligence, as expressed by the definition of a g factor and observed in larger, more complex animals.[citation needed] Early studies ca. 1930 found evidence both for and against such a g factor in rat.[23][24] Quoting Galsworthy, with regard to the affirmative 1935 Thorndike work:[25]

However, some more contemporary work has not supported the earlier affirmative view.[26] Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, series of articles have appeared attempting to address the question of general intelligence in this species, through measurements of tasks performed by rats and mice, e.g., with statistical evaluation by factor analysis, and seeking to correlate general intelligence and brain size (as is done with humans and primates),[medical citation needed][27] where the general conclusion was in the affirmative.[need quotation to verify][improper synthesis?][citation needed]

Social intelligence

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (January 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

A 2011 controlled study found that rats are actively prosocial.[28] They demonstrate apparent altruistic behaviour to other rats in experiments, including freeing them from cages: when presented with readily available chocolate chips, test subjects would first free the caged rat, and then share the food. All female rats in the study displayed this behaviour, while 30% of the males did not.[29][30]

As food

Rat meat is a food that, while taboo in some cultures, is a dietary staple in others.[31][32] Taboos include fears of disease or religious prohibition, but in many places, the high number of rats has led to their incorporation into the local diets.

In some cultures, rats are or have been limited as an acceptable form of food to a particular social or economic class. In the Mishmi culture of India, rats are essential to the traditional diet, as Mishmi women may eat no meat except fish, pork, wild birds and rats.[33] Conversely, the Musahar community in north India has commercialised rat farming as an exotic delicacy.[34] In the traditional cultures of the Hawaiians and the Polynesians, rat was an everyday food for commoners. When feasting, the Polynesian people of Rapa Nui could eat rat meat, but the king was not allowed to, due to the islanders' belief in his "state of sacredness" called tapu.[35] In studying precontact archaeological sites in Hawaii, archaeologists have found the concentration of the remains of rats associated with commoner households accounted for three times the animal remains associated with elite households. The rat bones found in all sites are fragmented, burned and covered in carbonized material, indicating the rats were eaten as food. The greater occurrence of rat remains associated with commoner households may indicate the elites of precontact Hawaii did not consume them as a matter of status or taste.[36]

France has several regions where people consume rat. A recipe for grilled rats, Bordeaux-style, calls for the use of alcoholic rats who live in wine cellars. These rats are skinned and eviscerated, brushed with a thick sauce of olive oil and crushed shallots, and grilled over a fire of broken wine barrels.[37][38][39][40][41]

Rat stew is consumed in American cuisine in the state of West Virginia.[42][43] In France and Victorian Britain rich people ate rat pie.[44] During food rationing due to World War II, British biologists ate laboratory rat, creamed.[45]

Rat meat is eaten in Vietnamese cuisine.[46][47][48][49][50][51] Rat-on-a-stick is a roasted rat dish consumed in Vietnam and Thailand.[52][53]

Bandicoot rats are an important food source among some peoples in Southeast Asia, and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimated rat meat makes up half the locally produced meat consumed in Ghana, where cane rats are farmed and hunted for their meat. African slaves in the American South were known to hunt wood rats (among other animals) to supplement their food rations,[56] and Aborigines along the coast in southern Queensland, Australia, regularly included rats in their diet.[57]

Ricefield rats (Rattus argentiventer) have traditionally been used as food in rice-producing regions such as Valencia, as immortalized by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez in his novel Cañas y barro. Along with eel and local beans known as garrafons, rata de marjal (marsh rat) is one of the main ingredients in traditional paella (later replaced by rabbit, chicken and seafood).[58] Ricefield rats are also consumed in the Philippines, the Isaan region of Thailand, and Cambodia. In late 2008, Reuters reported the price of rat meat had quadrupled in Cambodia, creating a hardship for the poor who could no longer afford it.

Elsewhere in the world, rat meat is considered diseased and unclean, socially unacceptable, or there are strong religious proscriptions against it. Islam and Kashrut traditions prohibit it, while both the Shipibo people of Peru and Sirionó people of Bolivia have cultural taboos against the eating of rats.[59][60]

Rats are a common food item for snakes, both in the wild, and as pets. Adult rat snakes and ball pythons, for example, are fed a diet of mostly rats in captivity. Rats are readily available (live or frozen) to individual snake owners, as well as to pet shops and reptile zoos, from many suppliers. In Britain, the government prohibited the feeding of any live mammal to another animal in 2007.[citation needed] The rule says the animal must be dead before it is given to the animal to eat. The rule was put into place mainly because of the pressure of the RSPCA and people who said the feeding of live animals was cruel.

Working rats

Rats have been used as working animals. Tasks for working rats include the sniffing of gunpowder residue, demining, acting and animal-assisted therapy.

For odor detection

Rats have a keen sense of smell and are easy to train. These characteristics have been employed, for example, by the Belgian non-governmental organization APOPO, which trains rats (specifically African giant pouched rats) to detect landmines and diagnose tuberculosis through smell.[22]

In the spread of disease

Rats can serve as zoonotic vectors for certain pathogens and thus spread disease, such as bubonic plague, Lassa fever, leptospirosis, and Hantavirus infection.[61]

As pests

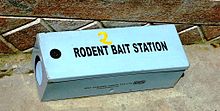

Rats have long been considered deadly pests. Once considered a modern myth, the rat flood in India has now been verified. Indeed, every fifty years, armies of bamboo rats descend upon rural areas and devour everything in their path.[62] Rats have long been held up as the chief villain in the spread of the Bubonic Plague,[63] however recent studies show that they alone could not account for the rapid spread of the disease through Europe in the Middle Ages.[64] Still, the Center for Disease Control does list nearly a dozen diseases[65] directly linked to rats. Most urban areas battle rat infestations. Rats in New York City are famous for their size and prevalence. The urban legend that the rat population in Manhattan equals that of its human population (a myth definitively refuted by Robert Sullivan in his book "Rats") speaks volumes about New Yorkers' awareness of the presence, and on occasion boldness and cleverness, of the rodents.[66] New York has specific regulations for getting rid of rats—multi-family residences and commercial businesses must use a specially trained and licensed exterminator.[67] Rats have the ability to swim up sewer pipes into toilets.[68][69] Rat infestations occur around pipes, behind walls and near garbage cans.

In the United States, cities tend to be breeding grounds for rat infestations and according to a 2015 study by the American Housing Survey (AHS) found that 18% of the homes in Philadelphia found evidence of rodents. This was followed by Boston, New York City, and then Washington DC as the cities with the largest rat and mouse problems.[70]

As invasive species

When introduced into locations where rats previously did not exist they can cause an enormous amount of environmental degradation. Rattus rattus, the black rat, is considered to be one of the world's worst invasive species.[71] Also known as the ship rat, it has been carried worldwide as a stowaway on sea-going vessels for millennia and has usually accompanied men to any new area visited or settled by human beings by sea. The similar but less aggressive species Rattus norvegicus, the brown rat or wharf rat, has also been carried worldwide by ships in recent centuries.

The ship or wharf rat has contributed to the extinction of many species of wildlife including birds, small mammals, reptiles, invertebrates, and plants, especially on islands. True ratsare omnivorous and capable of eating a wide range of plant and animal foods. True rats have a very high birth rate. When introduced to a new area, they quickly reproduce to take advantage of the new food supply. In particular, they prey on the eggs and young of forest birds, which on isolated islands often have no other predators and thus have no fear of predators.[72] Some experts believe that rats are to blame for between 40 percent and 60 percent of all seabird and reptile extinctions, with 90 percent of those occurring on islands. Thus man has indirectly caused the extinction of many species by accidentally introducing rats to new areas.[73]